The Amazon River Basin is one of the richest river systems in the world, covering more than 7-million square kilometers. This system contains more than 5600 species of fish and is home to large predators such as caiman, giant otters, and arapaima. Many of the species that occupy the Amazon River and its tributaries are endemic to these rivers (Lees et al., 2016). Inia geoffrensis, or the Amazon River dolphin (also known as: boto, bufeo, and fanjan by indigenous groups) is iconic of this river system and is found nowhere else in the world (Shostell & Ruiz-García, 2010).

I. geoffrensis is an elusive animal as the rivers that it occupies are often opaque and their erratic surfacing makes study impractical (Martin & da Silva, 2004). The difficulty surrounding the study of Inia has limited scientific inquiry and over the past 40 years, very little has been done to understand the genus apart from several population studies—mostly in regard to the dam construction and other anthropogenic barriers in the river—and genetic studies. Despite the challenges inherent in studying this species, indigenous groups and local people have intimate knowledge of these animals and, in some places, the dolphins are incorporated into local belief structures.

This paper will evaluate our current knowledge of Inia geoffrensis, both in regard to ecological and evolutionary knowledge, as well as the ways in which the river dolphin relate to the people and other organisms with which they live commensally. I will also consider the ways in which Amazon river dolphins are represented to the rest of the world through documentaries and other popular sources. Finally, I will consider the gaps in our understanding of how human/dolphin lives are co-constructed, both in places where these relationships are intimate and global, as perceptions are constituted and reconstituted by representations.

Becoming Inia

This section will engage with the ways in which Amazon River dolphins are transformed into objects of scientific inquiry. Through scientific analysis, the river dolphins are made into species, unmade, and reconstituted. The river dolphins are all at once static and synchronic entities, and dynamic and ecologically responsive. This entire process is a story of becoming with, in this case, the ways in which dolphins and scientists are made through mutual interpenetration.

Inia geoffrensis Description, Distribution, and Evolution

Amazon River dolphins are the largest predators in the Amazon fluvial system, adults measuring 2.6m and weighing 160kg on average. While commonly called Amazon Pink River Dolphins, they can range in color from pink to blueish-gray, and sometimes white (Fig. 1). Unlike oceanic dolphin species, I. geoffrensis has unfused cervical vertebrae which permits better navigation in tight underwater environments, filled with roots and forest debris (Ruiz-Garcia & Shostell, 2010). Amazon River dolphins have adapted to these murky and claustrophobic environments through a reduction in the size of their eyes and a reduction in the amplitude and increase in the sampling rates of their echolocation (Laegaard et al., 2015). I. geoffrensis is distinguished from all other dolphins—both oceanic and other river dolphins—by being the only identified genus of dolphins with heterodont dentition. While all other dolphins have conical teeth, I. geoffrensis has conical teeth in the front of their mouths and molar-like teeth—for crushing—in the rear.

Inia geoffrensis is social and are commonly found in small groups of 2-10 individuals with an average population density of between 0.21 and 1.55 individuals per linear kilometer. Ruiz-Garcia and Shostell (2010) recount a story of capturing a female Amazon River dolphin in order to relocate her to another part of the river for health reasons. After getting her into the research boat, five or six dolphins harassed the boat until the captured female was released. However, despite evidence of gregariousness and sociality, behavioral studies seem to indicate high levels of sex segregation and fierce competition among males for mates, often resulting in the deaths of young dolphins (Reeves & Martin, 2018). It should be noted that behavioral data is thin.

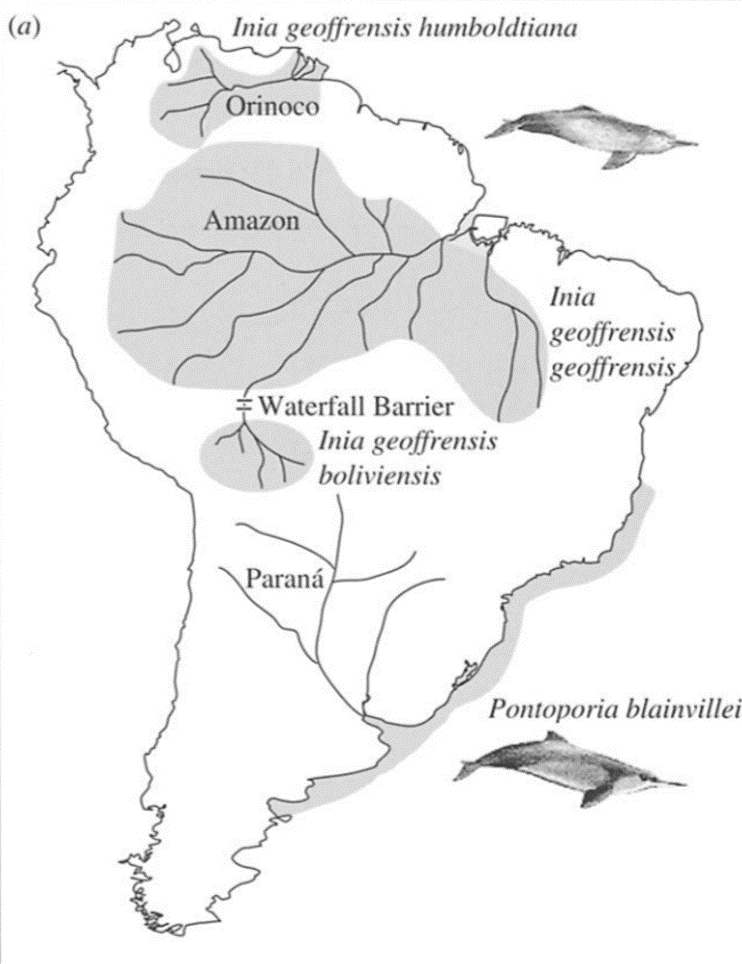

The description of the genus Inia is contentious. It was once divided into three distinct subspecies: I. g. geoffrensis, I. g. humboldtiana, and I. g. boliviensis (Fig. 2). However, with the introduction of genetics and more morphological data, these boundaries have been reconstituted. In the previous classification, I. g. geoffrensis described the populations of Amazon River dolphins that occupy the Amazon River Basin, ranging from Brazil through Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia across the fluvial system (Shostell & Ruiz-Garcia, 2010; Hamilton et al., 2001). This makes I. g. geoffrensis the most widely distributed of the former subspecies. I. g. humboldtiana described the Orinoco River populations of the species which inhabit northern South America and are isolated from the Amazon River Basin populations. The last former subspecies of I. g. boliviensis occupies the lower Amazon River, isolated from the main system by 400 km of waterfalls and rapids (Shostell & Ruiz-Garcia, 2010).

Inia g. humboldtiana has been reincorporated into I. geoffrensis and I. g. boliviensis is sometimes elevated to species (ITIS Report, 2019; Shostell & Ruiz-Garcia, 2010; Ruiz-Garcia et al., 2008). This is due to both morphological factors as well as genetic differentiation. The Orinoco River dolphins are now declared “data deficient” and are thus generalized within the species (Boede et al., 2018). I. boliviensis, while generally morphologically similar to I. geoffrensis, has more teeth, fewer phalanges, and other post-cranial skeletal differences. Recent molecular data also indicates that there is a lack of gene flow between the two species and the populations seem to have become isolated approximately 150,000 years ago (Shostell & Ruiz-Garcia, 2010).

The precarity of categories among Amazon River dolphins illustrates a greater aspect of scientific ways of knowing. In this form, individuals are constituted in groups which are constituted in populations which are bounded into subspecies, species, and genera. These are categories co-constructed by humans and the organisms of interest. Categories are co-constructed because the loci of classification are in the relation between the human and animals and not merely as a product of human action or a particular ontology of the animal. Other-than-human organisms are participants in how we come to make sense of them (Kirksey, 2015; Kirksey & Helmreich, 2010; Helmreich, 2004; Bulmer, 1967). Furthermore, these categories are generative, resulting in particular action in response to the connotations of the categories (Helmreich, 2005; Lowe, 2004). This kind of worlding is homogenizing, objectifying, alienating, and individuating (Castree, 2003). By worlding, I mean the creation and dissolution of boundaries resulting in new kinds of relations and interactions between organisms (Haraway, 2016; 2008).

The worlding that occurs between scientists and the river dolphins brought I. g. humboldtiana into being and made them a taxon of interest, with the possibility of conservation and research directed towards them. Erasing I. g. humboldtiana as a subspecies homogenizes it with the river dolphins occupying the Amazon River Basin. A potential consequence is that studying I. geoffrensis in one part of their range is just as good as studying in another. The challenges and cultural histories that are unique to some groups are rendered invisible in favor of more general concerns. Furthermore, species and subspecies-making are a kind of ecological commodification. The more inclusive the categories come to be; the more that conservation resources can be spread thin.

Current understanding of I. geoffrensis evolutionary history is limited. River dolphins (Amazon, Ganges, and Yangtze) form a polyphyletic clade (de Muizon et al., 2018); that is, they are grouped together but taxa are derived from multiple common ancestors (Fig. 3). While the three extant taxa of river dolphins share common ancestors, divergences occurred at different times with Ganges River dolphins diverging first and Amazon River dolphins diverging most recently from oceanic dolphins.

As river dolphin classification currently stands, they are grouped together despite not reflecting a phylogenetic relationship. This reflects an ecological account—occupying freshwater systems—instead of an evolutionary account. This way of classifying is more akin to “folk classifications” represented in work by Bulmer (1967) and Hunn (1982) than to purportedly objective scientific phylogenetic relationships. Bulmer (1967) presents the description and classification of the cassowary as it pertains to the Karam in New Guinea. The Karam classify the cassowary in regard to how it relates to a broader classificatory scheme, with cassowaries having human and other-than-human characteristics. Hunn (1982) argues that folk biological classifications reflect utilitarian cultural notions about which organisms are of greater importance.

For scientists, it is of greater value to group these species together due to their inhabiting similar environments: murky, hard-to-navigate freshwater bodies. River dolphins also have generally similar morphology: small eyes, unfused cervical vertebrae, and modified echolocation repertoire. Grouping river dolphins together serves a utilitarian purpose in a way illustrated by Hunn (1982) as this system, while not reflecting evolutionary history, carries with it a myriad of useful information. In this case, too, classificatory systems beyond phylogeny-building are a heuristically useful tool.

Inia geoffrensis and conservation

One way that the heuristic form of classification can be both useful and limiting is in conservation programs. Dolphins that occupy freshwater bodies experience unique challenges that oceanic dolphins do not experience. The nature and dynamics of riverine environments force human/more-than-human interactions that go beyond incidental interactions with people and come into contact with “modernity”: hydropower, big oil, and the trade in fish meat.

Amazon River dolphins are the most widely distributed freshwater dolphin species and are thus under various amounts of threat across their geographic range. Shostell and Ruiz-Garcia (2010) assert that Inia is probably the most secure of all the freshwater dolphins but are becoming increasingly threatened by anthropogenic activity. IUCN (2018) designates I. geoffrensis as endangered. While there are mediated action plans for the recovery of Amazon River dolphins, there is no established systematic monitoring scheme, likely due to the difficulty of creating demographies and the need for international collaboration. However, there is international legislation against the trade and killing of River dolphins.

Trujillo et al. (2010) outline the threats against Amazon River dolphin populations. Threats are broken down into two categories: direct and indirect. Direct threats include interactions with fishermen, bycatch, and deliberate killing. Interactions with fishermen revolve around competition for resources, which may result in wounding or killing dolphins to discourage them from coming into fishing waters. Bycatch is an accidental killing caused by dolphins becoming tangled in fishing nets and drowning. Finally, deliberate killing includes the intentional killing of dolphins, using the body to attract Mota catfish (Calophysus macropterus). Indirect killing includes habitat degradation marked by deforestation and overfishing, mercury pollution in waterways caused by gold mining, the construction of hydroways to facilitate travel and control flooding, and boat traffic and unregulated tourism as boat traffic disrupts dolphin behavior.

The most interrogated anthropogenic force affecting Amazon River dolphin populations is hydropower projects (Lees et al., 2016). The construction of dams in the Amazon fluvial system has fragmented the river and altered river dynamics (Fig. 4). River dolphins are segregated by dam infrastructure, and previously fast-moving bodies of water are transformed into still-water bodies, affecting fish distribution throughout the river. The fragmentation prevents gene flow through the River system, resulting in increasingly homogeneous populations, which could prove problematic for the long-term health and survival of river dolphins throughout their range.

Inia are bound up in the trade of catfish and food fraud. Fish fillets sold at Brazilian markets were suspected to be fraudulently labeled as a fictitious fish called “douradinha”. However, molecular analysis of the fish identified it as Calophysus macropterus, a necrophagus catfish that is generally seen as undesirable (Cunha et al., 2018). Inia are killed and used by fishermen to attract these catfish and then the fish are harvested. This was confirmed by the analysis of the stomach contents of recovered C. macropterus. Cunha et al. (2018) conclude in their study that exposure of fraud by journalists was a key piece in uncovering and enacting policy to combat the illegal use of dolphins in the fish trade.

Given the wide range of Inia distribution in South America and thus the highly variable threats against the species, I am selecting Ecuador as one example in which an action plan has been developed to address concerns for dolphin conservation (Utreras et al., 2010). I have selected Ecuador as this will likely be where I perform my dissertation research (Fig. 5). River dolphin conservation in Ecuador is challenged due to dispersed and discontinuous research that has left huge gaps in the broader health of dolphin populations throughout the country. There is a lack of formal strategy both in research and management, and so population studies are severely limited, especially outside of the northwestern portion of Ecuador. Furthermore, Uteras et al. (2010) claim that there is a shortage of qualified scientists interested in this species as they live in Ecuador. A broad survey of the literature indicates that there are very few studies referencing river dolphins in Ecuador and even fewer that specifically focus on Ecuadorian Inia.

A threat that, while not totally unique to Ecuador, is especially pronounced is damage caused by the oil industry (Utreras et al., 2010). This is manifested as acoustic pollution that interferes with dolphin echolocation in intraspecific communication. The more obvious threat from oil is the frequent oil spills that make their way into the waterways, polluting the waters and affecting the biodiversity of the area and indigenous people that make their homes along the rivers (Cepek, 2018). Since oil companies have entered into Cofán territory, billions of gallons of oil and produced water—untreated byproduct waste from drilling for oil—have polluted the waterways, resulting in substantially increased rates of diseases like cancers and a lack of clean drinking water among indigenous groups in the area. There has been no research performed to my knowledge of the effects of oil contamination on river dolphins in Ecuador, but it is likely a safe inference that it is having devastating consequences on dolphins and broader biodiversity.

Conservation is a human endeavor and, by doing so, places values and thus priorities on organisms demeaned worthy of conservation.The Action Plan for South American River Dolphins (Trujillo et al.,2010) makes a point to solidify the claim the Inia is an incredibly important keystone species for Amazonian waterways and is worthy of research and conservation resources. Despite this claim, in the ten years since this action plan was published, there has been little conservation research performed in Ecuador or in the broader Amazon River basin concerning river dolphins. Research has mostly focused on genetics, which, while it can be useful for conservation work—understanding genetic diversity within and between populations—is rarely presented as being centrally important for conservation.

Becoming Dolphin

The first part of this paper reflects the ways in which Amazon River dolphins (Boto) are transformed into scientific objects. I now want to attend to the ways in which Inia is made into Dolphin. I will follow Candace Slater’s (1994) capitalization of ‘Dolphin’ as well as ‘Boto’ to indicate the ways in which Amazon River dolphins are more-than-human beings instead of objects, either as objects of scientific inquiry or conservation. Here, I will present popular representations of Botos in English-language documentaries, popular media, literature, and on conservation websites. Finally, I will attend to the ways in which Botos came to have special relations with Amazonian cultures.

Popular representations of Boto

Scouring Netflix, Amazon Video, Smithsonian Channel, and Curiosity Stream, there is one documentary dedicated solely to Boto: “Mystery of the Pink Dolphin” (2016). This documentary focuses on scientists trying to understand the evolutionary history of Botos. The beginning of the documentary represents the Dolphins as “king of dark waters” (3:21), and the only reference in the documentary to humans that live alongside the Boto are presented as a threat: “the local human population has doubled in in the last thirty years… by depleting their food resources” (2:46-3:09). Botos are discussed in their relationship with humans as it relates to scientists and naturalists. Fossil hunters and biologists discuss what Botos are.

At one point in the documentary, the documentary shows the capture and study of a Botos. Biologist Vera da Silva discusses the extraction of milk from a nursing mother to determine the nutritional content relative to the size of the calf. It only shows how Botos are marked for scientific identification. This process entails holding down the Dolphin and branding it on its back, below where the dorsal fin would be, in order to facilitate behavioral studies (Fig. 6). Da Silva remarks that “[e]ven if the marking doesn’t seem to be a very pleasant process, it is indispensable to recognizing individuals and monitoring them long-term day-by-day so we may understand their social interactions and the details of their whereabouts” (41:30). This invokes Haraway’s (2008) notion of “shared suffering”. Haraway calls for the use of more-than-human animals in science to be responsive and make special effort to be “response-able” (Haraway, 2016), that is the “cultivation of the capacity of response in the context of living and dying in worlds for which one is for, with others” (Haraway, 2015: p. 231). This kind of relationship is not immediately apparent at first glance by da Silva states in regard to the process of catching, measuring, and marking that “stress is inevitable for the Dolphins and the researchers” (40:24). In this case then, there is a mutual suffering that occurs, the Dolphins suffer for the species and science while the scientists suffer out of compassion to the more-than-human collaborators.

“Mystery of the Pink Dolphin” (2016) is available streaming on Amazon Prime Video and so is available at no extra cost to Prime members. A brief review of the “Customer reviews” on Amazon are mostly distributed between five and four stars (34% and 31%, respectively). Written reviews focus on a variety of both positive and negative experiences of the viewers. Several reviewers indicated that the documentary was “very informative”, “good information”, and “educational,” while some negative reviews criticized the documentary for having “false information” (no elaboration) and “wacky evolutionary theories” (no elaboration). One particularly interesting review refers to the scene referenced above of capturing a mother and calf and branding, saying, “I was very disturbed by the capture of the mother and calf and the tests they did on them…”.

While this was the only documentary that I could find solely dedicated to Botos, they are represented in Planet Earth II (2016: 20:00) and a short clip from BBC Earth (2019). The documentaries’ footage referenced has one thing in common: they represent Botos in a “natural” context and without human settlement or activity. The only time the dolphins were shown in an anthropogenic context was when they were being shown as objects of scientific inquiry. All other footage presents them in pristine and unspoiled landscapes. However, as has been illustrated above, Botos live in highly anthropogenic spaces, surrounded by human settlements, dams, fishermen, oil refineries, and mining operations. The narrative thus perpetuates a sharp nature/culture divide, which obscures the ways in which Botos and humans are constituted in relation to one another.

A Google search of Botos yields a number of popular representations of Botos. World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has a species profile page that discusses general facts such as scientific name, size, habitat, and range. It also has a “Why They Matter” section that simply says, “River dolphins are rapidly disappearing, and so are their natural river habitats. Understanding the threats that impact them and protecting them ensures the preservation of their unique habitat.” This is followed by “Threats”, referring to pollution and human impacts, in particular, the killing of Dolphins for Mota catfish harvesting. Finally, there is a section titled “What WWF is Doing,” which states, “WWF works to protect river dolphin habitat in the Amazon region and continues to support river dolphin surveys to help determine their status and vulnerability. WWF also supports research about the impact of dams on the size and dispersal of dolphin populations” (WWF, N.D.).

The documentaries and WWF website construct one kind of narrative: Botos as an object of scientific interest and an important species in a biodiverse ecology. A sampling of books that focus on Botos tells a similar story but with an important distinction; there is also a mystical and magical character to the species. Furthermore, Journey of the Pink Dolphins: An Amazon Quest (Montgomery, 2000) and Encantado: Pink Dolphin of the Amazon (Montgomery, 2002) also explore the ways in which Botos are entangled with humans and a greater cosmology. These stories are illustrated in an ethnographic and historical work by Candace Slater, Dance of the Dolphin: Transformation and Disenchantment in the Amazonian Imagination (1994).

Dance of the Dolphin (1994) explores Brazilian oral history surrounding the Boto and the ways in which the Boto is simultaneously a real and mythical creature that has the ability to shapeshift into humans. The Dolphins are encantado or supernatural beings in the guise of Dolphins and they can bring about sickness or other misfortune to people with whom they come into contact. This contact most often occurs at festivals or community celebrations, where music and dancing take center stage. Botos love nothing more than to dance, and they use festas to seduce young men and women and attempt to lure them back to the underwater city Encante, from which very few people have ever returned.

When Botos transform into humans, they take on the form of White men and women: “Dolphins aren’t animals; they are a different kind of people—tall, blond, rich—another sort of gringo” (Slater, 1994: p. 202). Botas (female Dolphins) take on the form of beautiful women, seducing men, who, if they escape being taken to Encante, then may become weak, sick, unable to sleep, or a myriad of other maladies. This enchanted state requires pajés or shamanic healers to remedy the enchantment. Botos (male Dolphins) seduce young women, sometimes visiting them night after night. Women will sometimes become pregnant with the Botos’s offspring, resulting in half-human/half-Dolphin people that inhabit the local communities. Women can also be made enchanted through contact with the Dolphin, requiring a similar treatment from a pajé.

According to Slater (1994), the Dolphins represent “a refusal to assume an assigned niche within a stable, outwardly imposed order” (p. 2) and thus challenge conceptions of resistance as a conscious oppositional force. Instead, resistance in this context, in the face of national and global forces, is a “refusal to hold still” (p. 233). The Dolphin also challenges the boundary between the human world, the natural world, and the supernatural world. The Boto occupies multiple ontologies simultaneously and can be described by Kirksey’s (2015) “ontological amphibian” (See: Chapter 2: p. 17). They move freely through these forms of being and, through this act, also move humans across these culturally imposed boundaries, modifying the human umwelt by introducing hybrid human/Dolphin beings into the human world, bringing humans to the Encante, and leaving humans with the traces of encantado in the form of enchantments.

Hidden Under the Surface

Like the Amazon River, the ontology of Botos is murky. They are made into objects of scientific inquiry and, through this process, are individuated, valuated, and displaced (Castree, 2003). Science individuates Botos by removing them from the broader social and ecological context that they inhabit and instead conceiving them as individual objects of data. They are evaluated by transforming them into objects of conservation and biodiversity value. In this case, the Dolphins become a means rather than an end in themselves. Finally, science displaces them by constructing them in a way that privileges certain epistemologies over others, thus rendering many aspects of their being invisible or inexplicable to science.

Due to the processes of individuation, valuation, and displacement, much about the Boto is missed. The tangled webs of relations that are weaved through their interactions with other beings, both of the river and beyond it, are missed. It is attending to these entanglements that may elucidate more about the intentionality and ontology of the Dolphin, and the ultimate goal of Inia conservation can be more fully realized. Haraway (2016; 2015) argues that response-ability does not merely respond to but cultivates a capacity to the “context of living and dying in worlds for which one is for, with others” (Haraway, 2015: p. 231). To do this it requires attending to organisms as sym-poietic or “made together-with.” The studies that I have examined seem to brush against this idea but never commit to the idea seriously. Dolphins are affected by dams, fishermen, pollution, deforestation, climate change, and a multitude of other factors but are simply passive recipients in a narrative where the anthropogenic world imposes its force on the Dolphins. Questions arise from this sort of thinking, such as: 1) How do the Dolphins become with these anthropogenic factors. 2) How do they respond back?

Representations across different forms of media often present the Botos as natural beings, rarely being represented in the anthropogenic contexts in which they are often found. This elicits further questions. First, what does this communicate to the consumers of the representations? Ideas that the Dolphins exist far away from the touch of human activity belies the urgency that these animals desperately require. If the Dolphins are seen as remote, then there is potential for damage to effective conservation programs. Second, what might more contextual representations look like, and how might they be used to demonstrate the entangled sym-poietic nature of the Dolphins? I think this is particularly important as the nature/culture divide is still a ubiquitous framework in Western societies, and the more that notion is challenged, the sooner we can move on to thinking in more relational terms.

Finally, the one ethnographic work that I was able to find relating to the Dolphins takes seriously the cosmology of the people that live commensally with the Boto. Slater (2004) indicates time and again throughout the book that the people do not mean the Dolphins transform into people metaphorically; they actually become people and engage and further human/Dolphin hybrids. She takes this position seriously and attends to the literal nature of the stories that she is engaging with. However, the book is set in northern Brazil and so much of the range of the Boto is left out. More ethnographic work evaluating the relationships of the Dolphins to the humans and the knots that are tied would demonstrate the shifting natures of this relationship across the landscape. Work in Ecuador among indigenous groups would be of great interest to me as I hope to perform my dissertation work there and the literature is quite barren. Slater (2004) indicates that there are similarities in how people think with Botos across the Amazon, and this is something that seems interesting and worth exploring.

Due to the fact the Botos inhabit a world that is separated from our world by the surface of the water (Lien, 2015), which can both inhibit and enrich our conceptions of the Dolphins, it takes special effort to come to know them. Furthermore, the murky water obscures the lives of the Dolphins—they are mysterious and ephemeral—and this creates an exciting and challenging endeavor. Inia, Boto, Fanjan, encantado, and dancing Dolphins are all worth knowing, and to do so requires the dissolution of artificial barriers that demarcate them from humans and the rest of the world.

References:

BBC Earth. (2019). YouTube. Retrieved November 16, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yty9Zf8ie2g.

Boede, E. O., Mujica‐Jorquera, E., Boede, F., & Varela, C. (2018). Reproductive management of the Orinoco river dolphin Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana in Venezuela. International Zoo Yearbook, 52(1), 245-257.

Bulmer, R. (1967). Why is the cassowary not a bird? A problem of zoological taxonomy among the Karam of the New Guinea Highlands. Man, 2(1), 5-25.

Castree, N. (2003). Commodifying what nature?. Progress in human geography, 27(3), 273-297.

Cepek, M. L. (2018). Life in oil: Cofán survival in the petroleum fields of Amazonia. University of Texas Press.

Cunha, H. A., da Silva, V. M., Santos, T. E., Moreira, S. M., do Carmo, N. A., & Solé-Cava, A. M. (2015). When you get what you haven’t paid for: molecular identification of “Douradinha” fish fillets can help end the illegal use of river dolphins as bait in Brazil. Journal of Heredity, 106(S1), 565-572.

da Silva, V., Trujillo, F., Martin, A., Zerbini, A.N., Crespo, E., Aliaga-Rossel, E. & Reeves, R. 2018. Inia geoffrensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T10831A50358152.

de Muizon, C., Lambert, O., & Bianucci, G. (2018). River dolphins, evolution. In Encyclopedia of marine mammals (pp. 829-835). Academic Press.

Hamilton, H., Caballero, S., Collins, A. G., & Brownell Jr, R. L. (2001). Evolution of river dolphins. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 268(1466), 549-556.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulhucene. Donna Haraway in conversation with Martha Kenney. Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among aesthetics, politics, environments and epistemologies, 255-269.

Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet (Vol. 3). U of Minnesota Press.

Helmreich, S. (2005). How scientists think; about ‘natives’, for example. A problem of taxonomy among biologists of alien species in Hawaii. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 11(1), 107-128.

Hunn, Eugene. 1982. The Utilitarian Factor in Folk Biological Classification. American Anthropologist 84(4): 830-847

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). (2019). Retrieved November 09, 2019. http://www.itis.gov.

IUCN. (2018). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2018‐1.

Kirksey, E. (2015). Emergent ecologies. Duke University Press.

Kirksey, S. E., & Helmreich, S. (2010). The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cultural anthropology, 25(4), 545-576.

Ladegaard, M., Jensen, F. H., de Freitas, M., da Silva, V. M. F., & Madsen, P. T. (2015). Amazon river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) use a high-frequency short-range biosonar. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(19), 3091-3101.

Lees, A. C., Peres, C. A., Fearnside, P. M., Schneider, M., & Zuanon, J. A. (2016). Hydropower and the future of Amazonian biodiversity. Biodiversity and conservation, 25(3), 451-466.

Lien, M. E. (2015). Becoming salmon: aquaculture and the domestication of a fish (Vol. 55). Univ of California Press.

Lowe, C. (2004). Making the monkey: how the Togean macaque went from “new form” to “endemic species” in Indonesians’ conservation biology. Cultural Anthropology, 19(4), 491-516.

Martin, A. R., & da Silva, V. M. (2004). Number, seasonal movements, and residency characteristics of river dolphins in an Amazonian floodplain lake system. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 82(8), 1307-1315.

Montgomery, S. (2002). Encantado: Pink Dolphin of the Amazon. HMH Books for Young Readers Publishing. New York, New York.

Montgomery, S. (2000). Journey of the Pink Dolphins: An Amazon Quest. Simon & Schuster Publishing. New York, New York.

Reeves, R., & Martin, A. (2018). River Dolphins. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (pp. 827–829).

Ruiz-Garcia, M., & Shostell, J. (2010). Biology, evolution and conservation of river dolphins within South America and Asia. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Ruiz-Garcia, M., Caballero, S., Martinez-Agüero, M., & Shostell, J. M. (2008). Molecular differentiation among Inia geoffrensis and Inia boliviensis (Iniidae, Cetacea) by means of nuclear intron sequences. Population genetics research progress, 177-223.

Shostell, J. M., & Ruiz-García, M. (2010). An introduction to river dolphin species. Biology, evolution and conservation of river dolphins within South America and Asia. NOVA Science Publishers, New York, NY, 1-28.

Slater, C. (1994). Dance of the dolphin: transformation and disenchantment in the Amazonian imagination. University of Chicago Press.

Trujillo, F., Crespo, E., Van Damme, P. A., & Usma, J. S. (2010). The action plan for South American river dolphins 2010–2020. WWF, Fundación Omacha, WDS, WDCS, Solamac. Bogotá, DC, Comlombia. 249p.

Utreras, V., Suarez, E., & Jalil, S. (2010). Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis: A brief review of the ecology and conservation status of river dolphins in the Ecuadorian Amazon. The action plan for South American river dolphins, 2020, 59-81.

WWF. N.D. Amazon River Dolphin. Retrieved November 17, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/amazon-river-dolphin

Figures:

Figure 1. Shostell & Ruiz-Garcia, 2010. This picture illustrates the color and head shape of Inia geoffrensis.

Figure 2. Hamilton et al., 2001. This figure illustrates the geographical distribution of the three recognized subspecies of Inia geoffrensis.

Figure 3. de Muizon et al. 2018. Extant river dolphins include Platanistidae, Lipotoidea, and Iniidae. While the three share a common ancestor, many lineages are excluded from the classification.

Figure 4. Lees et al., 2016. This figure illustrates the completed, in-progress, and planned dams throughout Inia geoffrensis range at the time of publication.

Figure 5. Utreras et al., 2010. This map illustrates the distribution of Inia in Ecuadorian river systems. River 4 is the Aguarico, a primary river for dolphins and a river that runs through Cofán territory.

Figure 6. This is a screenshot of Mystery of the Pink Dolphin (2016), demonstrating the act of branding a captured Dolphin for scientific purposes.

The fist dolphin on top isn’t a river dolphin, but a tuxuci – an ocean dolphin species that lives in freshwater.

LikeLiked by 1 person