I spent part of the summer of 2025 in Kalama Conservancy, in northern Kenya’s Samburu County. The conservancy, part of the Gir Gir group ranch, covers 16,000 hectares (roughly 95,000 acres) of semi-arid savanna, acacia woodlands, and dramatic rocky outcrops. It lies between Samburu National Reserve and the Marsabit region, functioning as a vital wildlife corridor that allows animals to move between these landscapes in response to seasonal changes in forage and water.

The terrain is rugged and varied. Wide tracts of short-grass savanna stretch between granite outcrops, broken by stands of flat-topped acacia and clusters of commiphora shrubs. The soils are reddish and sandy, shaped by seasonal rains and long dry spells. During the wet season, ephemeral grasses carpet the ground, drawing wildlife and livestock. As the dry season progresses, vegetation thins, and the land shifts back toward muted browns and greys.

Wildlife and Ecological Role

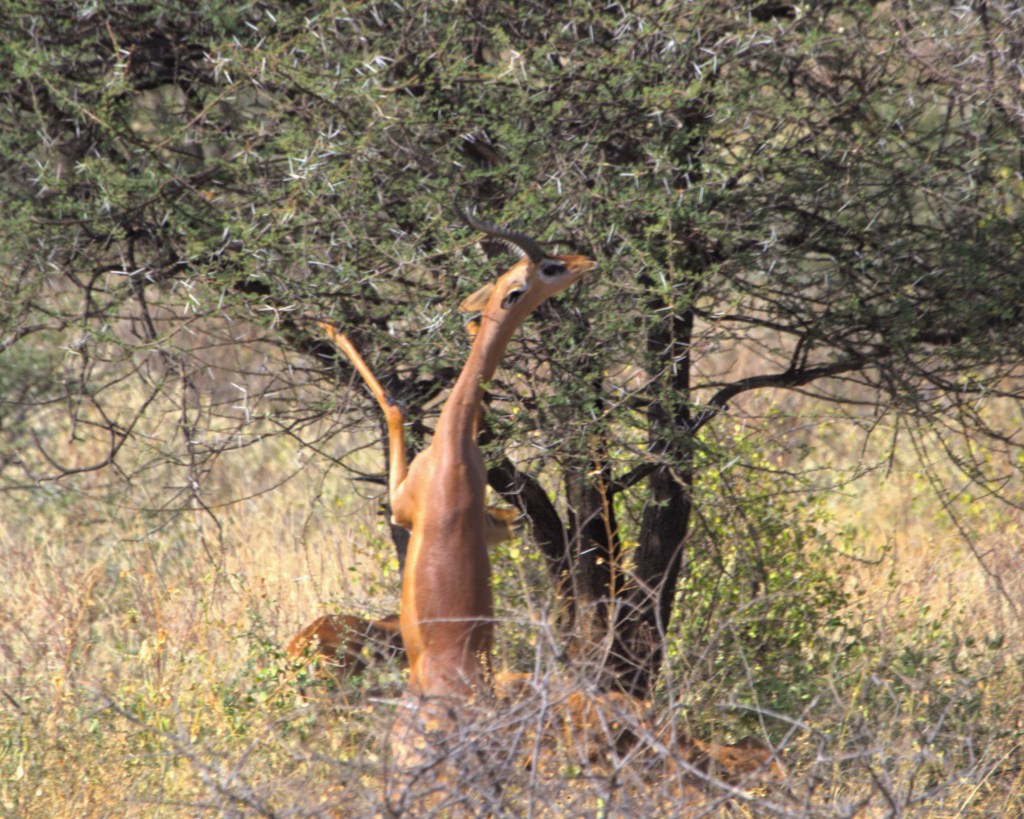

Kalama’s biodiversity is impressive given its arid climate. Endangered Grevy’s zebras graze in the open areas, while reticulated giraffes feed among the acacias. Beisa oryx, gerenuk, and dik-dik are common, each adapted to browsing sparse vegetation and going long periods without water. Elephants living in the conservancy in small family groups, using it as part of a larger migration route. During an excursion into the nearby Samburu National Reserve, we witnessed several herds of elephants gather at a river. Eventually, there were more than 50 elephants getting water, with the youngsters playing in the shallows. Lions, leopards, cheetahs, and hyenas patrol the peripheries, moving along the same corridors as their prey. Birdlife includes vulturine guineafowl, secretary birds, and various raptors that ride the thermals above the open plains.

A 6,000-hectare core zone is closed to grazing year-round, protecting critical breeding grounds and ensuring food availability for wildlife. Surrounding this is a buffer zone, opened to livestock only during the dry season. This management system sustains both ecological integrity and the pastoral economy, keeping grazing pressure in balance with vegetation recovery cycles.

The Loikop (Samburu) People

The Samburu are Maa-speaking pastoralists whose livelihoods and identities are built on herding cattle, goats, and camels. Cattle hold the highest value, economically and culturally. They are wealth stores, dowry payments, and symbols of prestige. Songs, proverbs, and ceremonies center on cattle, and decisions about grazing and mobility are often tied to ensuring their wellbeing. Goats and camels provide dietary diversity and resilience during droughts, when cattle herds may decline.

They live in homes called manyattas in family compounds known as bomas. These are circular enclosures made from thorn branches that keep livestock secure at night. Livestock are central to daily life: children are responsible for tending and moving smaller stock such as goats and calves, while older youth and adults manage larger herds. Young men in the warrior age-grade (morani) serve as both herders and protectors, carrying spears and sometimes clubs. Their role includes defending children and livestock from predators such as lions, leopards, and hyenas.

Living alongside predators is an accepted reality, and Kalama’s conservation structure helps turn that coexistence into an asset rather than a liability. The community’s grazing system, which is guided by elders and informed by deep knowledge of pasture conditions, rainfall patterns, and wildlife movements, reduces direct conflict by avoiding key predator habitats during sensitive times, such as denning or calving seasons. By protecting the core conservation area and opening the buffer zone only in the dry season, the Samburu ensure that prey species remain available to predators within secure habitat, reducing the incentive for predators to target livestock.

This approach blends cultural practice with conservation planning: predator presence is not eliminated but managed within a system that values both the livestock economy and the ecological health of the rangeland.

Community-led Conservation and Governance

Kalama’s land-use plan emerged through collaboration between the Samburu community and conservation partners, including the Northern Rangelands Trust. While outside partners provide technical support, funding channels, and tourism marketing, ultimate decisions about grazing zones, enforcement, and tourism operations remain in the community’s hands. This balance ensures that conservation is locally owned and benefits flow directly to those managing the land.

Eco-tourism is a major revenue stream. Lodges like Saruni Samburu and mobile safaris like Royal African Safaris employ local residents and channel visitor fees into community accounts. Tourism revenue supports schools, healthcare, water projects, and ranger salaries. Anti-poaching patrols, often staffed by local youth, protect wildlife as a community asset. Because people see a direct link between healthy wildlife populations and improvements in daily life, there is a strong incentive to maintain conservation commitments.

Why This Matters for West Texas Wolf Recovery

The Kalama model offers clear, practical lessons for predator recovery in a place as complex as West Texas. In Texas, private landownership accounts for nearly all rural acreage, meaning that any large-scale conservation initiative must operate within the rights and priorities of landowners. This reality shapes every aspect of wolf reintroduction. While conservation easements and science-led frameworks have preserved critical habitats in Texas, they often do not address the everyday realities of ranching communities managing livestock where predators roam. Without direct benefits, tolerance for reintroduced predators remains low.

Wolves, like lions in Samburu, require extensive, connected landscapes to survive. They need secure breeding areas where human disturbance is minimal, as well as enough prey to sustain populations without increasing livestock depredation. In Kalama, the community-led zoning system achieves this balance. The 6,000-hectare core conservation area remains completely off-limits to grazing year-round, giving lions and other predators safe habitat. Surrounding buffer zones open only during the dry season, allowing pastoralists to use the land without depleting resources critical to wildlife. This seasonal rotation ensures that predators have consistent access to wild prey, which reduces livestock losses.

In West Texas, a similar approach could designate wolf denning zones and key hunting grounds as core areas, closed to livestock at critical times. Buffer areas could be managed for low-conflict grazing, rotating herds in and out to avoid overlap with wolf activity during sensitive periods such as pup-rearing. Ranchers would have a clear role in determining where these zones are placed and how seasonal rotations work, ensuring the system reflects local knowledge of the land.

Economic incentives are central to this equation. In Kalama, tourism is the bridge between conservation and livelihood, with wildlife as the primary draw. West Texas would require a tailored incentive structure:

- Wildlife tourism could focus on wolves as part of a broader “wild Texas” experience, bundling predator viewing with other ecological attractions.

- Direct conservation payments could compensate landowners for maintaining wolf-friendly habitat and participating in seasonal grazing agreements. These programs already exist.

- Infrastructure investments, such as water improvements, fencing modifications, or predator-proof enclosures, could be tied to participation in the program.

All of these incentives would need to be negotiated collaboratively with landowners and local communities. The key lesson from Kalama is that outside partners like conservation NGOs, state agencies, or tourism operators can provide technical expertise, funding, and logistical support, but final land-use decisions must remain with the community. When residents are the ones who determine how land is used, and when they see direct benefits from healthy predator populations, tolerance shifts from reluctant acceptance to active stewardship.

In West Texas, where predator politics have long been contentious, this integration of local authority with supportive partnerships could mean the difference between a short-lived reintroduction effort and a lasting, self-sustaining wolf population..

An Integrated Future

Kalama shows that conservation is most effective when it is shaped through genuine collaboration between local communities and supportive partners, with final authority resting in the hands of those who live and work on the land. By embedding biodiversity protection within a system that sustains livelihoods, the conservancy maintains both ecological health and social stability.

In West Texas, adopting this model could transform wolf recovery from a contentious, top-down mandate into a locally driven opportunity. Aligning ecological and economic priorities and ensuring local voices lead in decision-making could make the difference between resistance and lasting success for the Mexican wolf.

Moving forward, my goals is to further my relationship with communities in Kalama and begin a research project that investigates how Samburu people accommodate, live with, and maintain conviviality with the predators and large wildlife species they share the conservancy with.

Read More:

Kalama Community Wildlife Conservancy

Leave a comment